Protect Yourself From Hidden Fees

As companies pile on sneaky fees that result in higher bills, CR gives you tactics to spot and avoid them

There’s the West Chester, Pa., woman irate over the $25 broadcast and sports fees she pays every month though she never watches sports—and about the $150 cancellation fee when she quit her provider.

Or the traveler in Texas who found that every time he went through a highway toll, the car-rental company dinged him $15 on top of the toll price, leading to an extra $90 in “administrative fees.” “They will charge $15 to process even a 31 cent toll charge,” he says. “Completely ridiculous!”

How about the music lover in Charlotte, N.C., shocked to find that after fees were added in, his concert ticket actually cost $123.18, not $99.95. Why can’t it be that “the price shown is the price paid?” he wanted to know.

Those are just three of the roughly 3,480 Americans who wrote to Consumer Reports over the past 13 months angry about the growing number of fees showing up on their bills, all as part of CR’s “What the Fee?!” campaign. “And more stories keep coming every day,” says Anna Laitin, director of financial policy at CR. “The stories show just how many fees people face, and how frustrating people find them.”

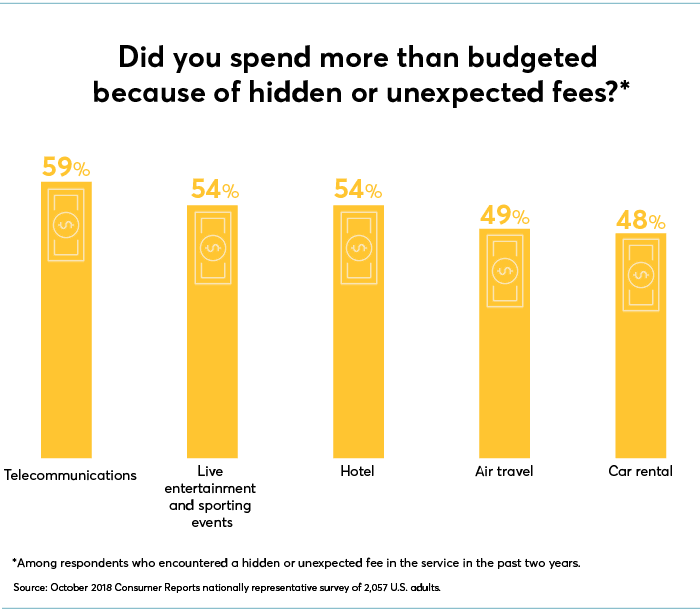

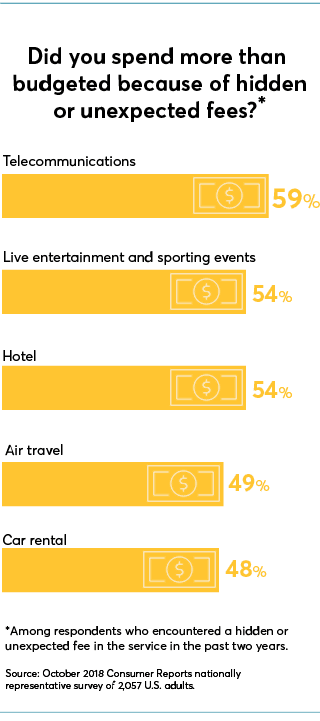

At least 85 percent of Americans have encountered an unexpected or hidden fee over the past two years for a service they had used, according to a recent nationally representative CR survey of more than 2,000 U.S. adults. And two-thirds of them say they are paying more now in surprise charges than they did five years ago.

As you might expect, almost everyone—96 percent—finds them annoying. “I’d like to find one of the 4 percent of people who doesn’t mind these fees,” Laitin says. “Maybe an airline exec?”

Today these extra charges are being added to more and more transactions—hidden in the fine print of a contract, popping up when you reach the last page of an online purchase, or combined with taxes or other costs.

And those tacked-on fees—some small, some large, but none that you recall being alerted about—can make you feel taken advantage of, especially when they add up, as they often do, to a lot of extra money.

The good news is that in many cases it’s possible to fight back against fees, and win.

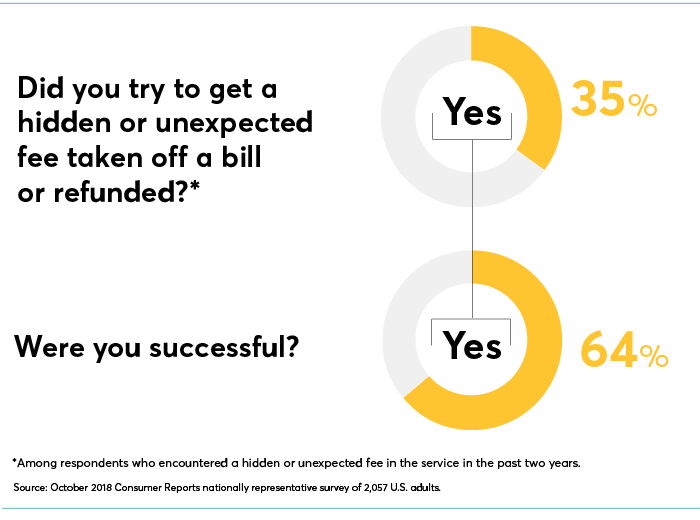

For example, 3 out of 10 people in CR’s survey who experienced a hidden charge in the past two years said they fought it—and almost two-thirds of those people said they were successful in getting the charge refunded or taken off the bill.

Recently in South Carolina, Duke Energy sharply scaled back a proposed 238 percent hike to the company’s fixed fee—the amount you have to pay regardless of how much energy you use—after customers, along with CR and other groups, complained to the state utility commission.

Consumers are also battling against cable TV fees, which along with cell-phone and internet fees were the most commonly reported extra charge in CR’s survey. Almost 140,000 cable TV subscribers around the country recently signed a CR petition demanding that cable providers eliminate add-on fees and advertise only the service’s total price. And in response to a CR request, nearly 3,000 people actually sent us copies of their cable bills so that we could better understand exactly how these charges affect consumers.

What Are We Being Charged Extra For?

The explosion in add-on fees may be an outgrowth of the rise of online shopping websites such as Expedia and Hotels.com, which allow consumers to quickly compare prices from multiple sellers and to zero in on the cheapest options. That stepped-up price competition has helped to lower prices for many goods and services.

But there’s an unintended consequence: As companies strive to become the lowest-price provider, they have a powerful incentive to make their prices appear lower, often by labeling a portion of the cost as a fee, says Glenn Ellison, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who has studied online pricing. When disguised as fees, these costs may not be picked up by online shopping portal engines, though some websites may eventually capture them.

To be sure, as long as fees are disclosed somewhere in the shopping process, consumers can, theoretically, calculate their true costs. But the reality is that add-on fees can be difficult to spot, requiring consumers to click through multiple web pages or scour fine print to get the information—a gradual reveal strategy that economists call drip pricing.

And few Americans today—many of them juggling jobs and families—have the time, energy, or desire to research a potential $30 fee, says Devin Fergus, professor of history, black studies, and public affairs at the University of Missouri and author of “Land of the Fee” (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Drip pricing works, too. “Once people have spent time searching a price, they are less likely to start over when they see the fees,” says Vicki Morwitz, a professor of marketing at the New York University Stern School of Business. “They often mistakenly assume competitors will have the same fees,” she says.

That consumer inertia was demonstrated in a 2018 study using data from StubHub, the third-party ticketing agency. In 2015 StubHub ran a pricing experiment, in which one group of shoppers was shown the full ticket price up front, including fees, and a second group saw those charges only at the end, when they made a purchase. People who saw fees at the back end spent almost 21 percent more than those who received all-in prices at the start.

Following this experiment, StubHub changed its default setting to show fees at the back end, although customers still have an option to see all-in prices. “It’s clear consumers want options . . . so we made sure they can see prices with or without fees,” says Alison Salcedo, a spokesperson for StubHub.

Consumers also tend to make calculation errors when they add up the total cost of fees, according to a recent study by researchers at the University of Chicago and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

The researchers gave participants three options: a disclosure that added all the fees into one price, a complex disclosure that listed the price and fees separately, and a combination that listed the price and fees separately but also showed the total. Though the combo option was the most popular, most participants liked the complex presentation better than the simple all-in price, says Shannon Michelle White, the study’s lead researcher.

But participants who were shown complex disclosures when trying to identify a lower-cost product often failed, with roughly half choosing a more expensive product. By contrast, most of those who received all-in-one disclosures correctly identified the low-cost versions.

“Up to a point, people prefer more complexity in disclosures, which they view as more transparent,” says White. “But that preference can lead them to paying higher fees because they are also overconfident about their ability to do math.”

A Year in Fees: One Family's Story

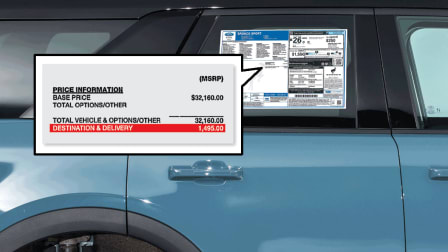

We estimated what an American family — two parents and two kids in Pittsburgh — might spend over the course of one year in fees associated with entertainment, travel, and a new car. Other fees not included here include those related to banking, credit cards, utilities, and more.

FEES

How to Fight Back—and Win

A few years ago, federal regulators cracked down, at least somewhat, on companies that didn’t disclose their fees up front. The 2009 Credit Card Act, for instance, required banks to disclose fee changes and interest rate hikes in advance. And in 2012, following a Federal Trade Commission conference on drip pricing, the agency sent a warning letter to hotel operators reminding them to disclose resort fees.

But in recent years, there has been little regulatory action to rein in fees. The FTC declined to comment for this article, and the CFPB did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

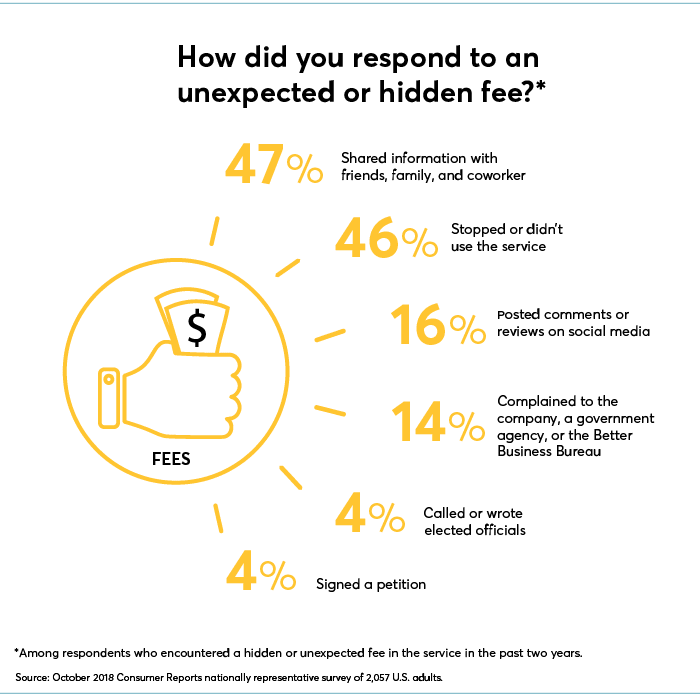

Still, as CR’s survey showed, consumers themselves are starting to push back. Fourteen percent of them said they had filed a complaint about fees with a company, a government agency, or the Better Business Bureau. And 16 percent said they posted comments or reviews about their experience on social media.

The first step in fighting back is recognizing fees in the first place. And with more and more Americans paying bills automatically, that doesn’t always happen. So it’s important to review your statements periodically.

“To avoid being overwhelmed, pick a bill or spending category every month, and review them for unexpected charges,” says Bob Sullivan, an independent journalist and author of “Gotcha Capitalism” (Ballantine Books, 2007). Over a year, “you’ll have a good picture of your finances, and you’ll probably catch a few surprise fees,” he says.

CR’s finance experts are pushing for reform, to make the marketplace fairer. “Fees should not be used to hide price increases,” Laitin says. “All fees consumers must pay to get a product or service should be wrapped up into the base price.”

Until that happens, though, consumers need to be vigilant. So we asked CR’s car, electronics, financial, and utility experts which sneaky fees to watch out for, and for tips on how to beat them.

What the Fee?!

Are you tired of the endless stream of add-on charges that appear on your bills? On the TV show "Consumer 101," Consumer Reports' expert explains to host Jack Rico how to avoid these pesky fees.

Editor's Note: This article also appeared in the July 2019 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.