How to Use Apple's Privacy Labels for Apps

The information, inspired by food nutrition labels, tells you how apps collect your data but can be tricky to read and understand

Apple unveiled new privacy labels in its App Store this week, which give consumers a detailed look at what personal information apps are collecting and how that data is used.

Apple is requiring the labels for any new app and for updates to existing apps. That means they’ll be widespread in the near future, but most apps don’t have the labels for now. They are visible in the app store on computers and iPhones once you’ve updated to the latest operating systems.

The change will give many consumers a first look at what apps are gathering, and with a little guidance, you can use this information to make more informed choices about which apps you install.

“Inspired by the convenience and readability of food nutrition labels, the information offered includes the types of data the apps might collect—such as contact information, or location—and whether they are shared with third parties for tracking,” Apple wrote in a blog post that announced the change in November.

What You’ll See, and What It Means

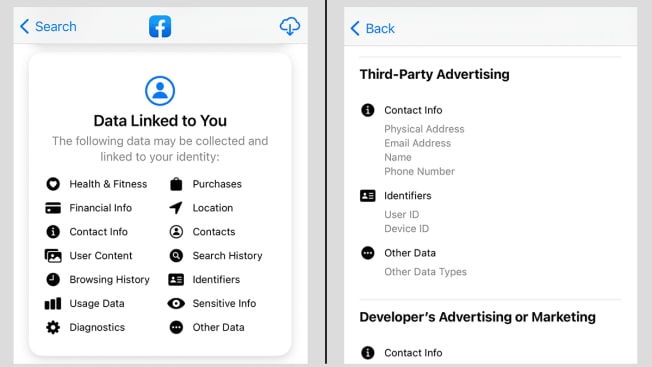

Some apps might not collect any information at all. But in most cases, apps will get up to three categories of labels, depending on the practices of the app in question: “Data Used To Track You,” “Data Linked To You,” and “Data Not Linked To You.” That could be confusing at first, but there are meaningful differences.

Data Used To Track You is all the information that apps and third-party companies use to identify people across multiple apps or devices. The email address you use to sign up for Instagram on your phone might be the same one you use to log in to the eBay website on your computer, for example. Data that might be less familiar to many consumers, such as unique ID numbers associated with your phone, can be used in the same way.

Consumers often worry about the bad privacy practices of one app or a particular company. But behind the scenes, tracking technology lets the tech industry build a web of information that connects data from multiple sources. Linking details about your interests and behavior to your phone’s ID numbers, IP addresses, WiFi information, and other seemingly innocuous data is one of the key mechanisms that allows companies to track you around the web.

Data Linked To You includes information, such as location data, that the app connects to you by tying it to identifiable details, such as your username, phone number, and the unique device information described above.

Data Not Linked To You is information collected by the app that is supposed to be stripped of any details that can tie that data back to a user.

Within those three categories, you’ll see up to 14 kinds of data that apps might collect, including your browsing history, contact information, financial information, and location.

You can get even more information by tapping “See Details.” For instance, an app collecting “User Content” might spell out that this includes information such as texts, photos, or customer support data.

Some of these entries are cryptic. You wouldn’t know that “Other financial info” means things such as your income or debts unless you read through Apple’s technical guidance for developers, where the specific terms are defined. You also can’t see a list of exactly where an app is sending your data—typically, information is transmitted not only to the app developer but also to a range of business partners.

Still, the new privacy labels provide much more detail than what has been available to consumers in the past, except through investigations of specific apps by Consumer Reports and other journalism and research organizations.

It might not be obvious which pieces of data you should care the most about. Data like your phone’s unique ID numbers might not seem sensitive on paper, “but people need to be concerned about how those details can link other sensitive information together,” says Pardis Emami-Naeini, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington who has studied privacy labels.

If a dating app or a women’s fertility app collects such an ID number, for example, that information could be linked to you behind the scenes and used to show you ads on a gaming app, or on a website you visit on your laptop.

apple apple

How to Compare Apps

One of the most useful ways to use these privacy labels once they’re prevalent across the app store will probably be to compare between multiple apps that do roughly the same thing. For instance, you might want to compare cooking or time-management apps to see which collects the least data on you.

Apple hasn’t announced any plans to roll out a tool that will let you contrast apps side by side, and the company didn’t respond to CR’s questions. But with a little manual effort, you’ll be able to see the differences in what apps collect.

Sometimes the privacy labels will be remarkably similar, but in other cases the differences are stark. As one Twitter user pointed out, the privacy label for the messaging app WhatsApp shows that the app can collect a wide variety of information, such as location data and purchase history, while the label for Signal, a competitor, says that app collects only contact information.

“Generally, you should look at what’s collected and think about why this type of app needs to collect this information,” Cranor says. A few years ago, a flashlight app stirred up controversy because it was hoovering up location data and other details. “If you’re downloading a flashlight and it wants to know your date of birth, that’s wrong. If a map app needs your location, it’s not surprising,” she says.

However, you may need to download an app and play with it before you have a clear understanding of whether the data collection is appropriate. “Sometimes you’ll need to experiment with the app before you pass judgment,” Cranor says. It may sound sketchy for a shopping app to access your photos, but it makes sense if it app has a barcode scanner you didn’t know about.

Consumers should also be aware that the privacy label might not tell you the whole story. “Individual data points are seemingly meaningless by themselves, but deeply personal things can be inferred when they are looked at in the aggregate,” says Serge Egelman, a digital security and privacy researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies how apps gather consumer data. (Egelman is one of the founders of AppCensus, a company that frequently works with Consumer Reports on studies of tracking in Android apps.)

Your browsing history or even a record of your location information could reveal all sorts of things about you, such as your gender identity, religious affiliation, or home address.

“When your device is leaking identifiers and saying what apps you’re using and websites you’re visiting, it’s a lot like if every business took a picture of your license plate when you pulled into the parking lot,” Egelman says. Your license plate number doesn’t say much on its own, but if it’s used to track your behavior, a detailed picture emerges. Egelman says consumers should think critically about how information could be used once it’s gathered and disseminated.

Pushing App Companies to Change

For now, the new labels could help people decide which apps to download, but consumer advocates hope the labels will help reform company behavior, too.

“In order for competition to happen on privacy, people have to be aware of what’s actually going on, or there’s no hope for apps differentiating themselves,” Cranor says. “It will be a delayed reaction, but it creates an opportunity for developers to stand out by improving their privacy practices.”

The labels should also help privacy experts and regulators hold bad actors accountable. “Privacy policies are so ambiguous, it’s hard to say whether a given unexpected use of personal data actually contradicts an app’s policies,” Egelman says. Forcing developers to be more transparent could make it easier to judge whether they are living up to their commitments.

Finally, requiring developers to provide the information Apple uses to create the labels could make the companies learn more about how their own products work. Counterintuitively, many companies don’t know all the things their apps do with your data, because most app developers reuse libraries of code written by other people to perform common tasks or insert functions related to third-party services.

That means apps often snatch up personal information and send it to third parties, without the app’s own developers knowing about it.

Until recently, consumers who wanted to learn about how their data was being used generally had few options beyond reading obtuse privacy policies. “Now the burden is being appropriately placed back on the developers,” Egelman says. “It’s a step in the right direction.”

However, he argues that telling people that many apps collect more data than they realize isn’t enough. Ultimately, Egelman says, Apple and other platforms also need to develop new, stricter policies that ensure consumers are being protected.